The Vagus Nerve: An Introductory Guide

I got interested in the vagus nerve and The Polyvagal Theory by Stephen Porges about a year ago.

This was when I dove deep into topics like trauma, depression and practices like Breathwork.

I discovered that the vagus nerve is an important part in understanding the science of stress, the stress response in our bodies and how the nervous system works. I was surprised that I had never heard much about it before.

Actually, I did hear about it a few times from a befriended naturopath who was helping me heal my SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth). She kept telling me to do humming meditation to activate my vagus nerve, but I didn’t take it very seriously and didn’t believe it would be effective. So I didn’t even try.

Nice one, Conni.

Looking back, it’s kind of funny how ignorant and clueless I was (insert facepalm emoji here).

A name that gets dropped a lot is Stephen Porges - he put the nerve on the map and did a lot of the first initial research on the vagus nerve.

What Does the Vagus Nerve Do and Where is it?

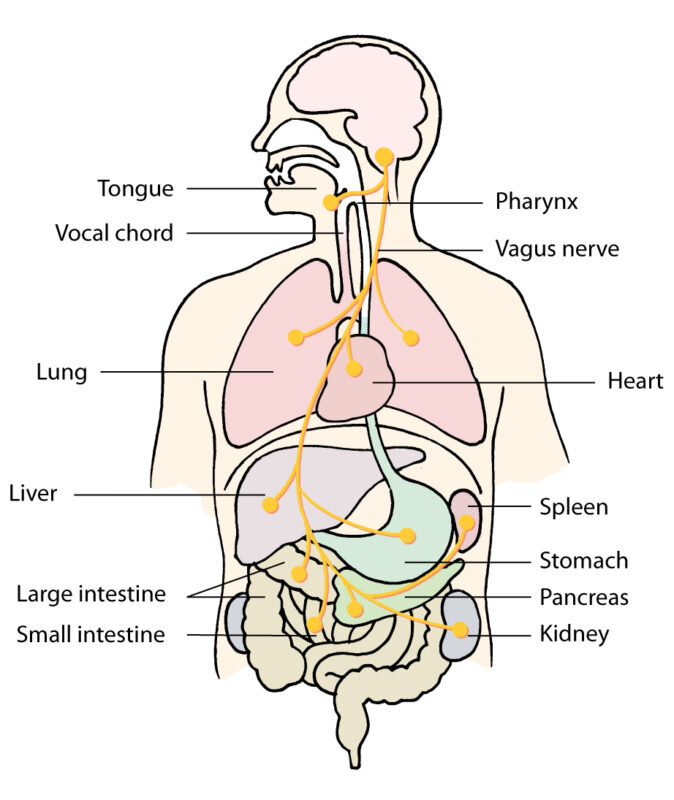

The vagus nerve is a squiggly, shaggy, branching nerve (in yellow in the image above) connecting your brain to many important organs throughout the body, including the gut (intestines, stomach), heart and lungs.

It’s in charge of turning off the ‘fight or flight’ reflex’. When stimulated, it basically acts as a brake on the stress response.

So it’s kind of a big deal.

It is the longest nerve in the body, and technically it comes as a pair of two vagus nerves, one for the front side of the body and one for the back side.

It’s called “vagus” because it wanders, like a vagrant, among the organs.

The vagus nerve has been described as largely responsible for the mind-body connection, for its role as a mediator between thinking and feeling.

So when people say ‘trust your gut’, it really means ‘trust your vagus nerve’.

The vagus nerve is basically listening to the way we breathe, and it sends the brain and the heart whatever message our breath indicates. Breathing slowly, for instance, reduces the oxygen demands of the heart muscle (the myocardium), and our heart rate drops.

Vagus Nerve and Stress Response

When I talk about stress, I mean everything that activates our nervous system and puts us into fight/flight/freeze triggered by fear, anxiety, anger, grief or overwhelm due to issues we face in relationships, at work or otherwise.

Your stress response is the collection of physiological changes that occur when you face a perceived threat, that is when you face situations where you feel the demands outweigh your resources to successfully cope.

Here is how stress works in a nutshell:

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) consists of the sympathetic part (SNS = activation, stress and exercise) and the parasympathetic part (PNS = relaxation, rest and digest).

When we feel fear or anger, our sympathetic nervous system gets triggered and charges up energy in the body, getting us ready to fight or flight. The SNS signals the adrenal glands to release hormones called adrenalin and cortisol.

Once the crisis is over, the body usually returns to the pre-emergency, unstressed state. This recovery is facilitated by the PNS, which generally has opposing effects to the SNS.

When the autonomic nervous system charges up, we can discharge energy via vagus nerve stimulation, as increasing your vagal tone activates the parasympathetic nervous system. Having a higher vagal tone means that your body can relax faster after stress.

The vagus nerve is essentially the queen of the parasympathetic nervous system — a.k.a. the chill out one — so the more we do things that activate it, like deep breathing, the more we banish the effects of the sympathetic nervous system — a.k.a. the “do something!” stress-releasing adrenaline/cortisol one.

It’s important to dissolve core tensions out of the nervous system and close the cycle of an emotional or stressful experience, as any overwhelming experience that doesn’t get digested in the moment lodges in the nervous system as some form of tension. The more this happens and the more of this tension energy we keep stored in our bodies, the more likely we are to develop chronic health issues, depression and anxiety.

Vagal Tone: Measuring The Quality of the Vagus Nerve

The vagal tone tell us how healthy, strong, and functional the nerve is:

when it is toned down you might suffer from anxiety, depression, and autoimmune issues.

when it is toned up, you are resilient, you bounce back easier from challenges, your moods more stable, and you have a strong immune system.

One way is to measure heart rate variability (HRV) — it’s a sort of “surrogate” for measuring actual vagal tone.

Heart rate variability is the amount that the heart rate fluctuates between a breath in (when it naturally speeds up) and a breath out (when it naturally slows down).

(Did you know? Stimulation of the nervous system occurs during each cycle of the breath. Inhalation emphasizes sympathetic activity (the stress/exercise branch and activation), and exhalation stimulates the parasympathetic activity (the relaxation, rest, and digestion branch).

Heart rate rises on the inhale and falls on the exhale, and the difference between those two rates essentially measures vagal tone.

When we stimulate our vagus nerve, we can reduce stress, anxiety, anger, and inflammation by activating the relaxation response of our parasympathetic nervous system.

What is The Polyvagal Theory?

Stephen Porges is the mind behind the fascinating Polyvagal Theory, which has massive implications for the treatment of anxiety, depression, trauma, and autism.

The theory has provided supercool new insights into the way our autonomic nervous system unconsciously mediates social engagement, trust, and intimacy.

Polyvagal theory (poly- "many" + vagal "wandering") is a collection of evolutionary, neuroscientific and psychological claims pertaining to the role of the vagus nerve in emotion regulation, social connection and fear response.

Here is a research paper on it by Porges and two books:

Irene Lyon is a trauma and nervous system specialist, whose video is a great introduction the theory:

Vagus Nerve Stimulation Practices and Exercises

In order tone up your vagal tone and relax your nervous system, here are some very powerful and effective things you can do:

Deep and slow diaphragmatic breathing into your belly (especially longer exhalations, such as using the 4-7-8 technique or 1:2 ratio, but also box breathing on a 4 or 5 count and coherence breathing with six breaths per minutes, which is 5 in and 5 out)

—> a recent study shows that just two minutes of deep breathing with longer exhalation engages the vagus nerve and increases HRVSinging, chanting and gargling

Cold exposure (eg. taking a cold shower, splashing cold water on your face and sauna)

Meditation

Exercise (especially weight lifting, HIIT, cardio and daily walking for 30-60 minutes)

Socializing and laughing

Here are a few more practices to generally calm your nervous system:

Massage (especially foot massage)

Body scan and Yoga Nidra

Massaging your diaphragm

Foam rolling and Yin Yoga (to work with tension in the fascia)

Transformational Breathwork

Sound Healing

Further Resources:

Jessica Maguire on Instagram

Irene Lyon on YouTube

A Vagus Nerve Survival Guide to Combat Fight-or-Flight Urges (great article series)

The Polyvagal Theory: The New Science of Safety and Trauma (video)